- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

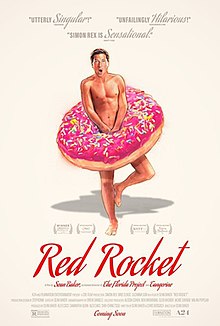

Movie Miscellany: 5 (New Order, Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore, Red Rocket)

New Order (dir. Michel Franco, 2020)

Michel Franco is possessed of an unusually literary sensibility, combining the sad warmth of Eduardo Galeano with an unwavering urge to record the relentless, patriarchal brutalities involved in death squad capitalism, reminiscent of Roberto Bolaño. This taut, nightmarish film lifts the painted veil, as it were, and translates the traumas and atrocities of recent Mexican history – including the 2014 mass kidnappings in Iguala, assumed to have been orchestrated by an organized crime ring in collusion with local police forces – into a visceral study in authoritarian butchery. The opening segment follows the soon-to-be-married Marianne (played with instinctive intelligence and subtlety by Naian González Norvind), as the pre-wedding-party celebrations at her wealthy, well connected family’s home are interrupted, and the unrest of the streets spills over into her world. “The rich are only defeated”, said the historian CLR James (writing of the Haitian revolution of the 1790s), “when running for their lives”, an adage that finds an echo in the insurrectionary radicalism of the poor and indigenous rioters who so shatter the lavish insulation of the upper-class gathering depicted here. It’s a sign of Franco’s probing control as a director, however, that the spare, heightened narrative pivots so naturally, in the sections that follow, to observing the horror and mercilessness of military dictatorship, itself a form of gangsterism, as the army high-command capitalises on the social unrest to consolidate its fascistic grip on state power, instituting gun-barrel rule. Even the naive but sympathetic Marianne, generously philanthropic in her relations with her family’s low-wage, in-house staff, is vulnerable to the intimate, murderous catastrophe that ensues, in a vision that no doubt will resonate with survivors of dictatorial, ‘free-market’ regimes from Chile to Argentina. The almost documentarian focus of the tale blends with the startling naturalism of the cast, so viewers are reminded, at every turn, of the violent, permeating force required for a culture of national silence (shadowed always by ‘the disappeared’ themselves) to be created and kept down: body by body, grief by grief.

Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore (dir. David Yates, 2022)

Among the self-assured, largely interchangeable English public school boys who have risen to cinematic greatness of late (Renedict Hiddlespatch), Eddie Redmayne is my personal favourite. For all his seeming thoughtfulness, Tom Hiddleston tends to inhabit the studied suavities of his most usual mode with the glazed expression of a man whose secret regret is not having run as a Lib Dem candidate in the most recent general election: the many fluencies of his style and persona seem, in brief, somewhat empty. Benedict Cumberbatch, on the other hand, approaches his work with the terse, focused professionalism of an engineer who just this morning added the final touches to his latest invention, his own gravitas: there's no ream of canonical verse or comic-book baloney this stern-eyed baritone won't saturate with 'meaning'. By contrast, Eddie Redmayne, lacking the breezy muscularity of his fellows, is capable of a plausible softness; he is more awkward than urbane, and his ruminative presence on-screen as a result seems less a posture arising from his undeniable poshness than a (very likeable) resemblance to the real thing. In the Fantastic Beasts films, he brings a winning gentleness to Newt Scamander, a dorky, ecologically minded wizard who finds himself aligned with a fitful group of anti-fascist conspirators, determined to foil the genocidal schemes of Gellert Grindelwald (Johnny Depp/Mads Mikkelsen) and headed by the wise, impeccably liberal Albus Dumbledore (played by an impressive Jude Law). The plot lurches along, and is sometimes charming, if also prone to allegorical sententiousness and numbing bouts of green-screen-generated spell-craft. Nevertheless, the lessons imparted in this (by now self-spawning) franchise are salutary enough: not only that there's a great deal of magic to be found in our muggled world, but also that for these to survive (the magic, the muggles), values of human affection and environmental care must be combined in the form of direct, defensive action, and the politics of hatred resisted. That J. K. Rowling, the author of such a fable, has garnered a real-life reputation as an unrepentant transphobe may be taken as final proof, if any were needed, against personality cults of all varieties, literary and political.

Red Rocket (dir. Sean Baker, 2022)

A sharp, perturbing polaroid-reel of life in America’s badlands – their ruthless hustle and vivacious flux – Red Rocket confirms Sean Baker as one of the most audacious and humane of contemporary film-makers, matching the sometimes painful brilliance of The Florida Project (2017) and Tangerine (2015). Beautifully acted and powerfully affectionate, Tangerine was, by turns, a raucous, delicate, and vivid catwalk round the strip with sex workers Ms Sin-Dee (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez) and Alexandra (Mya Taylor); filmed on three iphone 5S devices, it was effortlessly fresh, innovative, and thoughtful, establishing Baker as a kind of TikTok-savvy Ken Loach, without the dogma. Red Rocket shares some of the energy and concerns of its predecessor, in its portrait of the “suitcase pimp” and burnt-out porn star Mikey Saber (the magnetic Simon Rex), as he leeches off his formerly estranged wife Lexi (Bree Elrod) in their Texas hometown, while covertly grooming the teenaged Strawberry (Suzanna Son), a Donut Shop-worker whom Mikey is convinced will be his “ticket” back into the porn industry in L.A.. Odious, charming, indefatigable, Mikey is both a victim of a dog-eat-dog society and a complex paragon of emptiness and manipulation, scavenging whatever scraps of hope and trust he can find in the lives of the people around him, whom he exploits with abandon. When Lexi’s impoverished, elderly mother, unable to pay her medical bills, quietly confronts her son-in-law with the question, “are you in this time?” (worried for her daughter’s relationship and well-being), the wreckage and intimate destructions of twenty-first-century capitalist society are laid bare: Mikey may well be capable of empathy and understanding, but he is (not illogically) unwilling to compromise his ‘dream’ by such indulgences. As in the obliquely comparable films of the Safdie brothers, the sheer verve and intensity of the marginal world Baker depicts, degraded and hopeless as it often is, has an effect of shock and unshakeable fascination. It’s movies like this that keep cinema alive.