- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

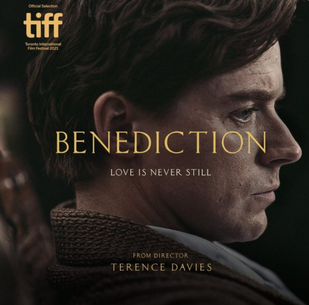

Movie Miscellany: 13 ( Benediction, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Succession [TV])

Benediction (dir. Terence Davies, 2021)

Benediction is best thought of as an intriguing failure. Ostensibly a biopic of poet and anti-war campaigner Siegfried Sassoon, the film is in fact a compilation of vignettes and conversations, some of which are more effectively handled than others. Peter Capaldi, badly miscast, takes a turn as the curmudgeonly bard in old age, contemplating a conversion to Catholicism; intended to be tragic, his portrayal of Sassoon as an embittered crank is inadvertently funny, a twitching caricature from a half-remembered pantomime. Evident budgetary restraints result in an uneven, sometimes amateurish tone and texture, qualities heightened by the script's strange mix of sentimentality and ponderousness. What saves the final effort – and what elevates it, in moments, to a powerful meditation on trauma and selfhood – is Jack Lowden's central performance as the young Sassoon, helped along by a talented background cast. Lowden has some of the anger, at once palpable and forcefully contained, that used to mark out Daniel Craig's performances in his early years; he seems to inhabit Sassoon's rigidity and sadness, his haughty charm and abiding pain as naturally as breathing. What's more, he reads Sassoon's poetry beautifully, investing it with all the anguish of its making. Nonetheless, the film never quite manages to synthesise its competing concerns. Davies is compassionately precise in recreating the repressive atmosphere of a harshly homophobic, post-war society. But he is also clearly nostalgic for this lost age, when wealthy bohemians made each other mellifluously unhappy, even as the callous disregard for human life and dignity shown by the British empire abroad had finally landed on home shores, as millions of men were methodically dispatched for slaughter during the First World War – all in the name of crown and country. These last categories are never sufficiently questioned by Davies (and the same is true of much of the commemorative culture now surrounding the century-old conflict): even in the depths of historical mourning, a patriotic wistfulness persists.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2011)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is known for bringing a granular focus to bear on local characters co-existing in remote corners of Turkish society. He is also a novelistic director, scaling his films to the rhythm of the land and its seasons, as they billow mutely around the warped and tangled lives to which he bears witness. Over the course of his dramas, small fissures of emotional strain begin to widen, so the initial drabness of his settings dissolves, coming to reveal vast panoramas of fear and yearning. Here, a small convoy of police, legal and medical officers must locate the corpse of a recent murder victim, whose haggard, haunted killer they have already apprehended, and who accompanies them on their search. The intensity with which Ceylan observes the men who dominate this film is enthralling; we somehow enter their lives, recognising with familiarity their humour and pettiness, their incompetence and vanity, the private hopes and sorrows they harbour inside themselves. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is a multi-faceted work: a police procedural, a modernised Shakespearean fable of sleepless nights and shadowy violence, a quietly accumulated study in regret and longing, and – in its subtle, deep-rooted fashion– a portrait of the nation. In a remarkable cast, Muhammet Uzuner is noteworthy for the sad dignity he brings to the role of the dutiful, observant, softly disillusioned Doctor Cemal; Firat Tanis, likewise, is outstanding as the taciturn criminal, weighed down with grief and thinned out by despair. Ceylan has an almost subterranean sense of time's passage: of the weight and inexorability of the past. But there's also a searching stoicism to his approach; he never tires of showing us the beauty and brokenness of human faces, in the changing light of our days.

Succession (created by Jesse Armstrong, 2018-2023)

One of the triumphs of contemporary television, Succession is a portrait of a dysfunctional family in freefall, and a riotous parable of the American way. The plot is simple: Logan Roy (Brian Cox) is the founder and head of a global news and entertainment corporation; his children and business associates want to know who will inherit his empire when he steps down, which may be sooner rather than later. Over four seasons, we have the terrible pleasure of observing this awful, oddly fascinating group of people as they compete for the final prize. There are a number of compulsive tensions driving the show. Tom (Matthew Macfadyen) and Siobhán (Sarah Snook) are in love, but only in the sense that they need, betray, and understand one another with an intimate ferocity that never quite abates. The Roy brothers, Kendall (Jeremy Strong) and Rome (Kieran Culkin), are at once infantile and charismatic, destructively ambitious and childishly vulnerable, continually teetering on the brink of either lift-off or personal break-down – usually both. Cousin Greg (Nicholas Braun), of “Greglet” fame, would be the bungling clown of the troupe, were he not so insidiously cunning. At the grizzled heart of it all is Logan, CEO and patriarch, who proves he's alive by attacking the universe, everything that exists. With his relentless, Machiavellian intelligence and aggressive distrust of human nature, he seems like a kind of word-made-flesh of American capitalism; he is also, of course, a crownless king and a deeply lonely man, eaten up by emptiness. As its title suggests, the show is consumed with the question of what comes next, and shadowed by the hunch that the answer is, “nothing good”. The truer reply might be, “more of the same.” The greed, fury, mendacity, exploitation that the would-be successors attempt to wield and deploy to their own advantage are vivid forces in our society. Like it or not, we live in Logan's world.