- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

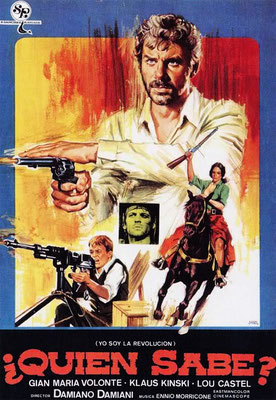

Movie Miscellany: 10 (Avatar: The Way of Water, A Bullet for the General, Rio Grande)

Avatar: The Way of Water (dir. James Cameron, 2022)

After a decade and a half of Marvel movies – with their cohort of infantilised, glibly militaristic superstars permanently posing and pouting before a green screen – James Cameron’s Avatar franchise feels fresh, and oddly wholesome. The entire enterprise, admittedly, glorifies CGI as the way of the cinematic future, but the effects are far more convincing in detail, and more spectacular in scale and scope, than anything so far disgorged by the increasingly bloated Marvelverse. In Avatar: The Way of Water, Cameron’s sky-blue protagonists, thinly sketched though they often are, have the virtue of existing in meaningful relationship with one another; they are capable of curiosity, intelligent concern for their loved ones, and self-reflection in changing circumstances – none of which, really, can be said of Marvel’s long conveyor-belt of photo-shopped ‘heroes’ and superfluous sidekicks. One result is that whatever bombast The Way of Water indulges (e.g. in its pulse-catching battle scenes) is offset by the relative thoughtfulness of its premise, with its intertwined environmental and political concerns. In that respect, the film feels like something of a culmination-point in James Cameron’s career: as in Aliens (1986), the plot conveys a distrust of corporate greed, particularly when tethered to a quasi-colonial extractive industry prone to ecological tampering in newly ‘discovered’ habitats; the machines used by the humans for heavy-loading and doing battle with the otherwise more physically powerful Na’vi bear a resemblance to the imposing title-figure in The Terminator (1984); the avatars themselves, as well as the recurring trope of wide-eyed youths feeling like outsiders, recall the cyborg characters in the under-rated Alita: Battle Angel (2019), which Cameron co-scripted; the aquatic atmosphere of course harks back to The Abyss (1989); and we even witness the dramatic sinking of a maritime ship, which seems, inevitably, like a riff on Titanic (1997). Widely panned by critics (as too big, too long, too weird, too blue), Avatar: The Way of Water in fact marks a new departure for blockbuster cinema: an immense, thematically sophisticated meditation on a world in danger, and the resistance-from-below needed to change the tide.

A Bullet for the General (dir. Damiano Damiani, 1967)

Set during Mexico’s revolutionary decade (1910-1920), and following a ramshackle band of rebels, robbers, and gun-runners led by one El Chuncho (Gian Maria Volonté), Damiani’s cult western combines edgy radicalism with a grandiose awareness of its own entertainment value – giving it the kind of vibrancy and exaggeration that Quentin Tarantino likes to mimic, albeit in a revised form usually shorn of its politically rambunctious ingredients. Volonté, who is marvellous, resembles a dishevelled and combustible version of the art critic John Berger, in a sombrero. His character, Chuncho, is an impulsive mercenary with populist leanings and a fitful affection for the life he lives, as well as the ne’er-do-well friends he collects (and occasionally ditches) on his fast-firing escapades. Perhaps fittingly, given Chucho’s volatile nature, there’s a cluttered, whimsical quality to the film’s conflicting sympathies: to Chuncho’s blue-eyed preacher-brother (played with amusing intensity by Klaus Kinski), who is inspired by the knowledge that “Christ died between two thieves”; to the affable and violent Chuncho himself; to the dirt-poor villagers he helps and then abandons; to the revolutionaries he supplies with arms, staid and stand-offish though they appear in person; and to the soldiers his men hunt and execute without mercy. Throughout, Damiani’s direction has a slapdash elegance, lending instinctive poetry to the framing and visual style, while also keeping the momentum of the plot with the central renegades as they skirt the many battlegrounds of revolutionary Mexico. Two of the former are particularly fascinating: the reticent American mercenary, Bill ‘Niño’ Tate (Lou Castel), whose two-sidedness and glazed ruthlessness make him comparable to the similarly mercurial killer-for-hire, Sir William Walker (Marlon Brando), in the superior Burn! (1969); and the fiery and insightful Adelita (Martine Beswick), the one woman among the vagabonds, who respect and value her presence, in contrast to the aristocratic land-owner who raped her when she was fifteen. Rowdy and bloodthirsty though it often seems, Damiani makes a case for the heroic qualities of bandit justice – a subversive mode, which in a world of punishing inequalities, is worthy of celebration.

Rio Grande (dir. John Ford, 1950)

US cavalry commander Kirby Yorke (John Wayne) is faced with two crises simultaneously: the troublesome tribes he is tasked with monitoring have whipped up a rebellion he must quash; and his wife (the majestic Maureen O’Hara), whom he hasn’t seen in fifteen years, has arrived in camp after discovering that their son has been stationed in his father’s regiment. As the first plot-line suggests, the genocidist elements in Rio Grande are harsher than in Ford’s earlier pictures, so the film seems, jarringly, to mix the warm idealism of Stagecoach (1939) with the tortured vision of The Searchers (1955). The sequences heroising the role of the cavalry in securing the frontiers of American democracy – through ethnic cleansing and punitive counter-insurgency tactics against the indigenous rebels – are perfunctory and comparatively bland. By contrast, the film is at its most passionate in the sub-narratives it allows to flourish; in moments, indeed, the screen positively smoulders with what can only be described as longing. When two former horse-thieves pose as cadets and volunteer for training, the rowdy stunts that ensue are glorious. Likewise, when a federal marshal arrives on the scene, the regiment’s collective conspiracy to save one of the horse-thieves from arrest speaks to Ford’s touching, and sentimental, appreciation for society’s under-dogs and castaways (a dispensation notably unavailable, in this film, to Native Americans). The most haunting scene involves an impromptu rendition of the ballad, ‘Down by the Glenside’: as the soldiers gather and sing of “the bold Fenian men”, killed for their resistance to colonial rule in Ireland, the (mostly Irish-American) officers bow their heads in regretful silence. We see flickering on their faces what each has realised inwardly: that they have been fighting the wrong war, against the wrong enemy, dreaming all the time of a home they can no longer return to. It’s a complex emotion – with a range of political implications – and Ford, we sense, understands it deeply. Perhaps Orson Welles said it best: “With Ford… you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world, even though it may have been written by Mother Machree.”