- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

Deadwood: A Dialogue

In November, 2021, my friend Johnny (JF) and I (COR) decided to exchange some thoughts on the television show, Deadwood (2004-2007). The series is set during the 1870s in Deadwood, a frontier-town in the American midwest, before and after the region’s annexation by the Dakota Territory. The conversation below has been edited for concision and clarity.

Johnny is an activist and writer for Dublin’s Independent Left; his reviews can be read online at www.independentleft.ie/author/john-flynn.

COR: We’re here to chat about Deadwood, the HBO series created by David Milch, and first aired between 2004 and 2007. You recently re-watched it, and I caught up on it, belatedly, during the 2020 lockdown.

I thought we could begin by jumping in at the deep end: by talking about Deadwood as a western, but also as a kind of anti-western. The opening episode was directed by Walter Hill, previously known for films such as Wild Bill (1995) and The Long Riders (1980), so there’s a continuity there. Likewise, I think that the broad contours of the plot and characterisation will be familiar to anyone who knows the movies of Sam Peckinpah, Anthony Mann, etc. On the other hand, Deadwood seems, almost by design, to explode the cultural mythologies and narratives we associate with that genre. What do you think?

JF: The interesting thing is that it was meant to be based in Rome, initially: a show about cops in Nero’s Rome. Milch went to HBO, and they said “keep the themes, but change the time period.” So eventually he settled on The American West. The central theme was still about moving from chaos to civilization: everyone who’s coming to Deadwood (during a gold rush) is escaping from somewhere else, they’re misfits or outlaws. But the contradiction is that they’re coming here, hoping to make enough money, so that when the place gets absorbed into the United States proper, they’ll have had time to accumulate wealth, they’ll have an influence on the laws that are introduced, they’ll finally be able to ‘make it’. Al Swearengen (Ian McShane) – someone once called him “the Miltonic pimp” – has to keep so many things in play while staying focused on this strategy. In the first couple of episodes alone, the amount of violence he metes out is something else!

So you’re right that the show subverts its genre, but it still has all the codes of a western. The town has a stagecoach. There’s a continual threat of people coming in from outside, whether they’re Pinkertons, or Hearst himself (Gerald McRaney), the mining tycoon. Then there’s the law-man, Bullock (Timothy Olyphant), in the lawless town.

COR: It does have a kind of classical scale and immensity to it. I think you could almost read it as a history play, in the Shakespearean sense. Every character, whether they are morally mediocre or completely vicious, has a total dramatic presence, and an eloquence to match it. You mentioned the saloon-owner and pimp Al. There’s a rich vulgarity and violence to his language, as well as his whole view of the world. But he’s totally appealing as a character. Similarly with the hotelier E. B. Farnum (William Sanderson), whom I know you’re a fan of: he’s a spineless, casually cruel character, who has a wonderfully obsequious and pretentious way of speaking that somehow makes him a cherished persona in the overall drama.

JF: Farnum has some amazing monologues as the show goes on, and some horrible interactions with poor Richardson (Ralph Richeson), his exploited assistant. “Could you have been born, Richardson, or were you egg-hatched?”!

There are so many different routines in the show. It progresses from day to night. There are all the morning rituals (usually going to get a horrible breakfast at Farnum’s hotel). There are the daily meetings and encounters. You really get a sense of the town of Deadwood. Over time, it becomes very vivid, but also visceral: we see the town being formed, but also people pissing into piss-pots, Doc Cochran (Brad Dourif) coming to see the sex workers… Trixie (Paula Malcomson) literally spreads her legs on the bed so he can perform an operation on Alma Garret (Molly Parker), allowing him to examine the relevant anatomy in advance. Then there are the dead bodies being fed to the pigs at Wu’s (Keone Young). When Alma Garret wants to see Wild Bill, who’s been on a bender the night before, Jane (Robin Weigert) says to her, “it takes a while for the phlegm to settle.” There’s a tremendous physicality, a brutality, to this place.

COR: In many ways, Deadwood is a kind of nowhere. The show works by submerging its audience in this chaotic historical moment, when the American West is still in formation.

You introduced me to the work of J. Hoberman, the film critic, whose general idea as I understand it is that films mediate but also help to generate the nightmares and dreams, the fantasies and fixations, of the nation over time. If you were to apply that idea to Deadwood, it’s almost as if Milch is arguing, at the turn of the 21st century, that the only way you can make sense of the imperial hubris and butchery of contemporary history, as America’s so-called ‘forever wars’ are expanding around the world, is to go right back into the rotten core of the nation’s past.

JF: I think Hoberman means a number of things. He’s interested in how material life and cultural life feed into each other, how the spectacle of politics and the spectacle of culture become almost the same thing. Then he stretches it further, and starts to think about the medium itself, the way actors inhabit multiple roles over time that start to shadow another.

In this case, you have someone like Hearst being played by Gerald McRaney, who was famous for his very gentle role in Simon & Simon (1981-1989). That’s a huge burden, in a way. Hearst is so ruthless: he threatens Alma Garret, he has the Cornish union-workers, who are trying to organise, savagely murdered; but he’s still a fascinating charcter. It’s similar to what you were saying earlier. The show is consciously in communication with Walter Hill’s movies, for example, and other westerns. Keith Carradine, of course, was in The Long Riders, and appears here as Wild Bill Hickock.

And all that’s before we get to the literary echoes. Milch was a Yale scholar who worked on a four-volume history of American literature. He was also a research assistant to a famous biographer of Edith Wharton. Alma Garret, I think, seems to have stepped straight out of a novel by Edith Wharton or Henry James. It takes a while to understand the nuances of her situation: she’s been married off (to pay off her father’s debts) to an oily, supposedly respectable character, and now finds herself in this rough Western town, with no friends whatsoever. You can see why she needs laudanum, just to keep going.

COR: Keith Carradine brings a real pathos to Wild Bill, I think. When you’re watching him, you sense the loneliness and pain of this defeated icon. There’s something elegiac about his performance in those opening episodes; in a subtle way it draws you into the world of the show. We’re introduced to Deadwood through Wild Bill, by witnessing his decline.

JF: The first time we see him, he’s working off a hangover but he’s also spiritually exhausted. He keeps telling us how tired he is, and we know it’s not just a physical issue, it’s existential. But the portrayal is so complex. He’s not looking back to some halcyon time, when there was a true West filled with heroes. He’s just at the end of something, and there’s no meaning any more. So he gambles and boozes; he’s spent.

COR: He’s like a dead man walking. On the point you made about the actor playing Hearst having a back-history on-screen: Ray McKinnon, who appears as the epileptic preacher in Deadwood, later starred in Jeff Nichols’s movies, Take Shelter (2011) and Mud (2012). In a funny way, the gentleness and vulnerability of his role in the show seemed, to me, to ground those gnarly, inscrutable characters he went on to play.

JF: That’s true even within the show itself: Garret Dillahunt plays Jack McCall, who shoots Wild Bill, and then appears in a later season as Woolcott, Hearst’s geologist. It’s a complicated work of art: we can never just freeze-frame these characters. There’s also the fact that we see Al, a brutal person, always working strategically to counter the forces against him, but capable in moments of real tenderness.

COR: Doesn’t Victor Serge say somewhere that a writer will dedicate an entire novel to a single character whom a political ‘man-of-action’ would have to eliminate in a heartbeat? As you mentioned, Al is shrewd and ruthless, and totally immersed in the ecosystem of life and death as they play out over the show’s course.

Something you said also reminded me of how Hearst describes himself: claiming that he only cares about “the color”, meaning (in his case) gold. It seems like a brilliant, twisted adaptation of W. E. B. Du Bois’s identification of what he called “the color line”, meaning white supremacy or racism, that courses through American history. It’s almost as if Deadwood is suggesting that there’s an even deeper violence at the root.

JF: I think that’s true. I mean, it’s set in the Black Hills, one of the oldest geological marvels in the Americas, but the only rocks that Hearst and his men are interested in are gold. For the Lakota Sioux, those hills are sacred. Al’s line is that “it’s a bad time to be a dirt-worshipping heathen”: even the earth they venerate is being dug open. The mining operation is like a rape of the earth.

COR: That may relate to your point about Doc Cochran having to insinuate himself into the literal anatomy of the sex workers, as a way of perpetuating the strange nowhere that is Deadwood. It’s a gut-rooted vision that Milch has given us, but, as you say, there’s also that macro-scale in the background, which frames the immediate drama.

JF: I think we do see Du Bois’s “color line” there as well. The alcoholic, Steve (Michael Harney), is always saying the most appalling things, but nobody in the show is unredeemable. He’s in the mud, railing insanely about “the white man” carrying his burden through history: it’s such a tortured articulation of race hatred. And even with the people who don’t come across as overtly racist, we can see that they have certain assumptions they carry around with them. When Steve is raging, Hostetler (Richard Grant) calls the onlookers “motherfuckers!”, and you can tell from the way Bullock intervenes that his unspoken attitude is something like, you can’t say that to white people.

COR: That’s a brilliant observation. I’m intrigued by Bullock. He’s the reluctant law-man, righteous and incorruptible. But when we first encounter him he insists on personally breaking the neck of a jailbird he’s been chatting to, rather than handing him over to a posse that’s gathered outside the prison. From the outset he’s an unyielding, punitive kind of character… and this is the ‘good guy’!

JF: That scene is so complicated. Bullock is the personification of the laconic law-man: it’s not that he’s poor with words, but he distrusts them. So as he’s writing in his journal he gets stuck, and then the camera pivots to the guy being held in jail, who’s good with words, and begins to chat. They seem almost friendly with one another, and Bullock is rarely friendly with anybody!

COR: To the point of blandness, I would say. He sometimes seems like a caricature of the rigid, bellicose sheriff.

JF: I think that’s deliberate. If you notice his stance whenever he gets into that belligerent frame of mind, he seems almost to be mirroring a classic pose (tilted and striding) of Jimmy Stewart or Garry Cooper, preparing to administer justice. He’s constantly enacting a kind of transference of rage onto the people around him; he beats up anyone he dislikes.

COR: Is it fair to say that the show also declares war on Doris Day? The Calamity Jane we meet in Deadwood is combustible, hard-drinking, loyal, furious… in many respects, the polar opposite of Day’s version in the musical (1953).

JF: In Deadwood, she’s completely vulnerable, one of the most wonderful characters in the show. She’s terrified of Al, and also of his rival, Cy Tolliver (Powers Boothe), who is very menacing. But they don’t have to say anything, she just cracks into pieces when they come in.

COR: She’s traumatised in some way. She’s in pain.

JF: She takes every compliment as if it’s a threat. When Doc says to her, “you’ve got a gift”, she replies, “don’t be mean.” She’s the one who cares for that smallpox victim. She’s Doc’s helper.

COR: She has such grief for Wild Bill, too. There’s a real depth to her loss.

JF: In some ways that relates again to Carradine’s performance. It has a constant after-life in the show, we can remember him so clearly.

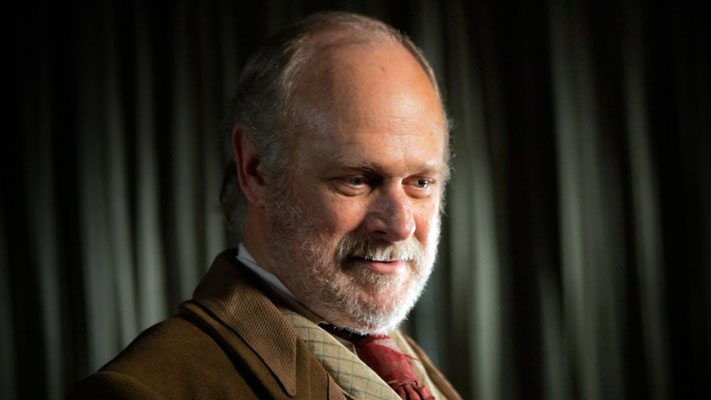

COR: Most of the characters have some kind of historical provenance or counterpart, is that right? I had presumed, for example, that Jack Langrishe (Brian Cox), the travelling thespian who arrives in the third season, was a riff on a similar character who features in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946), but he was a real figure: an actor who became one of the first state senators for Idaho, apparently. There’s a shadowing of real history all the way through.

JF: Yes. Seth Bullock did actually hang that jailbird in the way you mentioned, for example. And he was later a friend of Theodore Roosevelt. Doc Cochran, I think, is a composite of two real-life characters. I also think the Doc echoes Milch’s own father, who was a professor of surgery: very troubled but a great genius.

COR: Again, I had presumed that Doc Cochran was meant to be a variation on the disgraced or alcoholic doctors in John Ford’s movies. But I think you made the point to me once that Deadwood would have been impossible if Milch hadn’t been capable of identifying with each of his characters at some level.

JF: That’s absolutely true. Doc is a complex figure. But he also helps us to understand the town. Because of his job, he’s always straddling the various fault-lines and factions, he tends to everyone. And he sees some terrible things.

COR: It’s almost as if the ‘civilisation’ we explore in Deadwood is synonymous with violence, something primitive and ugly.

JF: We see how primitive accumulation leads to robber-barons, to great cities, to great wealth. It’s set in the mid- to late 1870s, a few years after the 1873 recession, which Alma Garret references at one point.

COR: I was going to ask you about the finale. The studio cancelled Deadwood prematurely, so Milch wasn’t given the opportunity to extend or conclude the show as he may have wanted to. Maybe this is my limitation as a viewer, but I was disappointed with the finish. I was expecting the seething conflict between Swearengen and Hearst to resolve itself through warfare, maybe along the lines of Heaven’s Gate (1980), or even The Wild Bunch (1969). But that particular scenario seemed to be consciously deferred or deflated at the close.

JF: I think there was definitely another season in the show. Al sometimes says he might just burn down the camp, and that’s what happened in reality: Deadwood burned to the ground. I think Milch must have envisioned some kind of conflagration at the end. We didn’t really get that in the movie (2019). Rewatching the show, I kept thinking of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), how the Warren Beatty character gets killed off-camera. It’s the final indignity. Deadwood has an element of that.

The strange thing is that the whole series seems to indulge in violence, misogyny, racism, the worst of the worst, and yet it would be an obvious distortion to label Deadwood an exploitative piece of work.

COR: I think part of what makes it so great is the way it brings hypocrisies and violences that are already latent in American entertainment right to the surface, and delivers them raw.

On a related note, we often hear about “the golden age of American television.” The Sopranos (1999-2007) and The Wire (2002-2008) are usually mentioned, but Deadwood is also a part of the same moment. I wanted to ask what you think sets it apart from those other shows, and why it can seem relatively under-appreciated even when ranked among them. I know you also have a soft spot for Donald Glover’s more recent series, Atlanta (2016-present).

JF: Maybe I’m wrong, but I think a lot of people don’t have much time for westerns. I used to love The Wire, the way it tries to offer a panoramic portrait of capitalism as it’s actually experienced. But in the age of #BlackLivesMatter I’ve found it more and more difficult to enjoy. Honestly, I think the age of cop shows has passed. The Wire is a brilliant drama, but at this distance it seems more limited than when it first came out.

We’re used to being given crude caricatures of black males in American television, which can be very tedious. But Atlanta is the opposite: it offers fully rounded, lyrical, fluent, sometimes comedic portrayals of (black) life, full of spontaneity and unpredictability. Deadwood has similar qualities, but in a more general way, I think.

COR: With Deadwood it’s still possible to feel an affection for particular characters while remaining aware of the sheer rot at the heart of American history.

JF: It’s so brutal and horrifying, and yet the main sensation you feel when you’re watching is a desire to experience it in-person: just being there, the violence and intensity of it, the realness and lack of heroism in it. And the language, of course, is brilliant throughout. As Milch says, “it’s the essence of our identity as human, that we speak.” The full force of that idea really strikes home in Deadwood.

COR: Ezra Pound once talked about trying to write “a poem containing history.” It’s a formulation that I think can be applied to Deadwood, but also to each of its individual characters. I like to think of Al Swearengen as a “poem containing history”.

JF: For me, Deadwood is the most thrilling exposition, through drama, of civilisation-in-the-making, with all its contradictions and brutalities laid bare. It has complexity, but also depth. It’s visually mesmerising. For me, it’s completely vivid: the best tv show there is.