- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

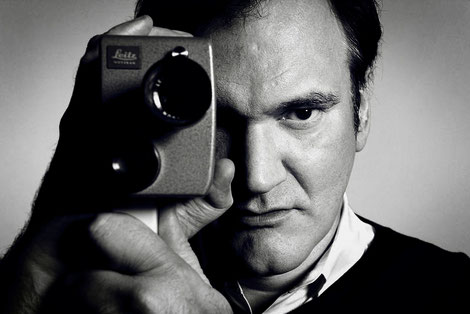

Cinema Speculation

(A review of Cinema Speculation by Quentin Tarantino, first published by Headstuff.org)

Quentin Tarantino has written a book of film criticism that looks like a memoir, and sounds like the script for a one-man show he never got around to making (and which nobody else would). Cinema Speculation is a chatty, provocative, strangely fatiguing soliloquy by an artist-geek intent on celebrating his own fixations; in its fizzing, rollicksome way, it’s also wacky, memorable, and affecting. The same could be said of many of his movies.

As a director and screenwriter, Tarantino’s great virtue is that he cares – madly, unrelentingly, with spoofy religiosity and cackling licentiousness – about cinema: the good, the bad and the ugly of it, from its most spectacular imaginative feats to its trashiest pornographic fantasies. He loves it all: sometimes more, we suspect, than life itself. This, in fact, is a question-mark that hovers over a great deal of his filmography. The loquacious, hilarious, occasionally psychopathic gangsters we encounter in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) were partly based, Scorsese has said, on guys he knew around town while growing up in Manhattan’s ‘Little Italy’ district, and it shows. By contrast, the nattering, blood-spattered heisters we meet in Reservoir Dogs (1992) are exaggerated riffs on stock characters Tarantino had previously absorbed from mid-century noir movies and 1970s revenge-flicks – virtuosic (re-)creations from the big screen, both compelling and contrived. For all the mayhem that unfolds around them, Scorsese’s characters seem authentically alive in a way that Tarantino’s rarely do.

If there tends to be an emotional emptiness wallowing just below the surface of Tarantino’s crackling visions, his formalism and compulsive referentiality nevertheless make him more dynamic than his many imitators (from Guy Ritchie to Ben Wheatley), whose penchant for casual blood-letting and chauvinist dialogue, lacking Tarantino’s cunning sense of cinematic purpose, feels gratuitous and dull. For all the loud obscenity of the material Tarantino frequently deals with, he is never unthinking: he toys incessantly with the idea that movies, designed primarily to entertain, offer viewers an alternative reality – which may be more or less just, more or less cruel, more or less arousing, than the one we already have – before testing the many subjectivities involved in such a prospect. A foot-fetishist’s idea of high art, for example, may bear little resemblance to that of a devotee of slasher films, just as the skull-cracking violence unleashed against members of the Manson Family on-screen differs, morally and actually, from the butchery committed by said killers in life. In Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood, Tarantino sees it as his role and right to twist such tensions to his own eccentric ends, on the basis that this is what directors have always done: from John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock to Don Siegel and Brian De Palma (all, tellingly, rather male and masculinist artisans of their trade). “It takes a magnificent filmmaker to thoroughly corrupt an audience”, he writes, with the cool flare of ambition in his eyes.

There is a cerebral kind of sophistication, and even a transgressive appeal, to such an outlook. Certainly Tarantino has proven adept at deploying, and then merrily capsizing, the notion of art for art’s sake, in an effort, as he puts it, to electrocute his “audience out of their movie-trope-fed complacency”. From another angle, however, to insist that cinema argue only and endlessly with itself – divorced from the actualities it plunders for inspiration, and devoid of the humanity it relies on to exist and continue – seems the very definition of conceitedness and superficiality. Tarantino has long been trapped inside this studio-box of mirroring contradictions, and seems happy enough to remain there.

For better or worse, Cinema Speculation feels like a book that only Tarantino could have written. This is because he writes as he talks, veering between ejaculatory ranting (often in praise of quasi-reactionary formula-flicks that “blew my fucking mind!”) and quiet ruminations, disarming in their sincerity and insight. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) is “one of the few perfect movies ever made”, we are told, and because of Tarantino’s free-wheeling cinephilia, we can almost believe him. As for that great (and sometimes controversial) wielder of deception and desire, Alfred Hitchcock, he was, Tarantino says, the master of “an aggressive cinema that manipulated audiences with both its fluid visual grammar and its (at times) savage wit”: a judgement as accurate as it is pithy.

One of the pleasures of reading these essays derives from their wild flights of fancy, which are invariably esoteric and often exhilarating. “I can see De Palma making a great version of Death Wish”, Tarantino yammers, “but probably with someone like Peter Falk or George C. Scott as its star (what a fucking dynamite picture that would have been!).” In this sprightly, bedazzled style of film “speculation”, even his tiresome and literalistic contention that depicting destructive behaviours (in a manner meant to enthral or excite) is not the same as committing such destruction in real terms, becomes interesting. Sam “Peckinpah’s violence constituted a turn away from mere brutality”, Tarantino notes, persuasively suggesting that the director’s slow-motion scenes of orgiastic killing were “closer to liquid ballet and visual poetry painted in crimson”: one reason, perhaps, why The Wild Bunch (1969) remains mesmerising to watch.

For all his garrulous affection for the under-rated and the second-rate – careening from John G. Avildsen’s Joe (1970), to Tobe Hooper’s The Funhouse (1981), to the Sissy Spacek comedy, Hard Promises (1990) – Tarantino is at his most compelling when he sets his sights on acknowledged classics. Like John Ford’s The Searchers (1954), he argues, Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) is “a movie about a racist” rather than “a racist movie”, but “what makes the film a gutsy masterpiece is it dares” the audience to query that distinction, and “then allows them to devise their own answer.” In a passage that could have been penned by Pauline Kael (a critic whose zinging verdicts Tarantino is often keen to resist), he elaborates:

… when you watch Taxi Driver, you become Travis Bickle. Regardless of whether or not you empathize or sympathize with the rituals of Travis’s existence, you observe them. And in observing them, you come to understand them. And when you understand this lonely man, he stops being a monster – if he ever was one to begin with.

Here, Tarantino speaks the intimate, illuminating language of the true aficionado: someone who has internalised the complexities, as well as the pleasures, of the films he loves. Bickle, he says, is only “one of many faceless people existing by themselves that big American cities are filled with”, people “living solitary lives, without family or friends or loved ones”. As a movie-maker, we know that Tarantino believes in his medium: in its power to awe, to shock, to titillate; to mock its own mythologies; to perfect, subvert and reinvent the genres it generates. As a critic, however, and especially in segments like the one above, he also proves capable of tapping into the very quality his own pictures so frequently lack: an inwardness, founded on empathy, and sure in the knowledge that there are other people out there who understand.

The final section of the book is the most affecting, dedicated to Floyd Ray Wilson: a drifter, movie-buff, and amateur screenwriter (who never ‘made it’), who for a short period in the 1970s was a friend of Tarantino’s mother, and used to take her film-addicted, teenaged son to double-bill screenings in Torrance city. Although the two didn’t stay in touch after Wilson moved on, without him, Tarantino reflects, the Oscar-winning Django Unchained would probably never have been written or made – not because Wilson had concocted the characters or sketched out the dialogue all those years earlier, but because his attitudes (to cinema, and to American culture and history), at once subversive and totally serious, had shaped Tarantino’s own. He didn’t thank him in his Oscar speech, Tarantino says, but he should have. It’s a generous note, but also an honest gesture of recognition and respect: from one fellow enthusiast to another, who shared a love of movies once, long ago, in the brutal, wondrous past.