- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

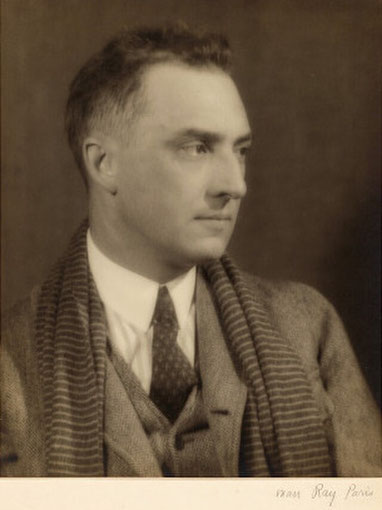

A Mosaic for Dr. Williams (1883-1963)

When the doctor dies the green world mourns. Word travels rapidly in all directions. On the banks of the Ganges, Allen Ginsberg paces, remembering the old man's kindness, his lively eyes and wizened hands. And the books he wrote. There's “life moving out of his pages”, the Beat-head says, “the poet / of the streets is a skeleton under the pavement now”. Far off, spring is brightening the grey, New Jersey stones. On the day of the burial, overlooking the flat slopes of Lyndhurst Cemetery, a wide, dark sedan mounts the curb. Improbably, ten fresh-rumpled figures emerge, dressed in black, in borrowed suits. Jim, the doctor's friend and publisher, watches the grand arrival, softly smiles. “They were the leading / Young poets of New York come / To pay homage to the great old / Poet they so much admired.”

~

Modernity requires verses, a doing-away with jaded modes. Deploring the decline and fragmentation of the new century, T. S. Eliot reaches for an answering form, a form of shining rhythms, melancholy shards. Marianne Moore opts for the fair and careful cataloguing of esoteric things, her every poem a pleasure garden, meticulously kept. Wallace Stevens, in turn, believes that “the great poem of the earth remains to be written”, a task he hasn't yet attempted (and never quite fulfils). Meanwhile, the doctor works his round, attending to his patients, attentive to their needs. He returns home daily, nightly, weary – and alert.

~

After dark, he mounts the steps, thinking through the day's events: the fevered children, mothers past their term, the work-men maimed or winded on the job. He mutters faintly to himself, not to wake the house. Dousing the lamps, he pauses, a creaking shadow by the bedroom door. A thought: “the imagination is an actual force comparable to electricity or steam”. He turns, retrieving his pad and pen, a hurry rising through him. He writes it out, a scratch of ink. Moments later, another: “What I put down of value will have this value: an escape from crude symbolism, the annihilation of strained associations, complicated ritualistic forms designed to separate the work from reality”. Something new is happening. Tingling with tiredness, elated, he lays his head on a midnight pillow, gives himself to the dreams that come.

~

“rooted, they / grip down and begin to awaken”

~

Readers make the poems their own. In time, they build a picture in their minds of this doctor-author, with his travelling-bag of verbal still-lifes and brick-smog pastorals. They like him; listening to him, his high, giddying voice, his vivacity and precision. “To Be Hungry Is To Be Great”, he cheers, scavenging the back-lots of sprawling factory-towns. Stick-lean himself, he wanders with purpose through rained-on spaces, streaming grime. His words graffiti the winter air. “I am moved to write poetry / for the warmth there is in it”, he declares. And we believe him.

~

The academics have their doubts. Exactly where does he think his language comes from, if not from England? “From the mouths of Polish mothers”, he replies. Literature is born in the streets, and belongs there. The language of the poem, the talk he hears in tenement-shacks, are one, the same. England, mellifluous and imperial, he detests.

~

According to Alec Marsh, the “resentment of the post-colonial writer is everywhere in Williams”, “when he speaks, as he frequently does, of setting words free he means to free them from the dead hand of the English colonizer.” For the Johns, Keats and Milton, however, the New Jersey bard makes a dual exception. Keats's “Endymion really woke me up”, he recalls with glee in his Autobiography. “Milton, the unrhymer”, he likewise salutes: as a fellow subversive of cultural norms, “singing among / the rest... // like a Communist”. Writers find their comrades where they will. They make their own traditions.

~

“I have eyes / that are made to see”

~

The more supercilious of his mates rib him repeatedly. Some immigrants, the joke (which may not be a joke) maintains, are more settled than others; have higher claims on the culture they share. “You have the naive credulity of a Co.Clare emigrant”, quips Ezra Pound, “But I (der grosse Ich) have the virus, the bacillus of the land in my blood, for nearly three bleating centuries.” Carlos, first name William, relishes the fun. He laughs; a bright, American sound.

~

“Say it, no ideas but in things”: a dynamic credo, once we recognise that the objects his poetic vision encompasses are rarely static. They bristle and fizz with energy, ready to spring to life and motion. This is true alike of the “white / chickens” strutting beside “red wheel / barrow”, glimpsed from a sickbed window; of the “small house with a soaring oak / leafless above it”, ignored by every passer-by but one; of the great “figure 5 / in gold / on a red / firetruck”, hurtling through the city. Noticing is not only a way of conferring a value on the disregarded and the disrepaired, but of establishing a relationship with these. Seeing activates meaning. To be a poet, open your eyes.

~

After studying a catalogue of Depression-era photographs by Walker Evans, he praises these tender, brutal “works of art” for the modern age, with “their own identity, their own flavor, their own breath by which they live for us”. Much of his own work can be thought of in photographic terms, literally a writing with light. The avid glance, the time-lapse-slow and detailed observation, the searching urge to document and register – all these are live components of his craft. By the same token, he suggests, Evans should be regarded a poet of the visual, a documentarian of the gaze.

~

“Proletarian Portrait” might be a parable, or the equivalent of a snapshot – perhaps both. In it, a “young, bareheaded woman” comes to a halt in a busy street, before reaching into her shoe and removing “the nail / That has been hurting her”. “Urban class struggles”, remarks Mike Davis, “especially those addressing emergencies of shelter, food, and fuel, were typically led by working-class mothers, the forgotten heroes of socialist history”. There is no indication that Williams's “Proletarian” is a mother. But she is far from being a mere icon, either. The actuality of her stance and movement, the bustle and materiality of the street she walks through, lend her a fully dimensional presence. She is centre-stage in a daily drama of to-and-fro, give-and-take. We may not know her name, but we behold her clearly. Usually a forbidding monolith, the proletariat now lives and breathes.

~

“In a case like this I know / quick action is the main thing”

~

When a military coup breaks out in Spain, the doctor takes a side. As chairman of local committee for medical aid to Spanish democracy, he lobbies and fundraises tirelessly for the loyalist cause. He may be the leading figure among the major American poets of his generation to oppose the Francoist cause, just as Langston Hughes and Muriel Rukeyser are in theirs. After the bombing of Guernica, he sends hand-written cards to every physician in Bergen county, New Jersey, requesting political or material support. Of the dozens he petitions, only one responds.

~

Sometimes a line will look us right in the eye, and proclaim: “It is all for you”. We understand more deeply then, attuned to the particulate connections between what we see and how we live. Everything humdrum, everything wasted, begins to flare, bright in a glaze of drifting rain. This is the poet's doing. The blasted world ruffles its wings, like a great, white rooster, yodelling dawn.

~

As a new, global conflict of unprecedented proportions gathers force, the doctor confesses in private to feeling despair as well as anger. “All we know”, he says, is that “we were too smug in our beliefs touching the ultimate triumph of man's coming humanity to man... too glib, too sanguine, too languid in what we thought and said and too doctrinaire in our praise and service.” During the second world war, he adopts a gruelling regimen of fourteen-hour working days, to cover the caseload of younger medical staff conscripted into the armed forces, for service overseas.

~

Poetry and democracy have enough in common for each to implicate the other in its practice. A poem might be thought of a receptacle for varied voices; an action in time; or what Williams calls “a social instrument”. Democracy, in essence, is much the same. In his early sixties, his medical career over, his own health teetering, he embarks on a long poem, Paterson, exploring such correlations. A quotidian epic in American-English (the “language which we hear spoken about us every day”) it will occupy him compulsively for the next two decades, until his death.

~

“What do I do? I listen... This is my entire occupation”

~

“The logicallity [sic.] of fascist rationalizations is soon going to kill him”, he writes of Pound, his friend from university, now a defender of Mussolini: “You can't argue away wanton slaughter of innocent women and children by the neo-scholasticism of a controlled economy program.” Afterwards, the killing done, he seeks out the grizzled maestro, and finds him no longer caged, but confined to quarters in St. Elizabeth's hospital, Washington. The two rough rams lock horns, renewing the battle, quarrelling with zest. They talk of essential things, good poetry and good government. They growl and yawp. Before he goes, Bill puts his hand on Ezra's shoulder. A small touch, to say what words cannot.

~

Interviewed in a New York periodical in 1964, Florence, addressed as Mrs Williams by her interlocutor, offers a concise summary of the dispute: “Bill and Ezra wrote quite a number of letters to each other when the war started; they were on such opposite sides. Ezra was definitely pro-Fascist, much as he may deny it, and Bill was just the opposite.” For some commentators, Florence – discerning, watchful, perennially self-effacing – is the hidden hero of Bill's story, his lifelong companion and unwavering supporter. “It is all / a celebration of the light”, he sings in a late love-poem, where memory blooms.

~

Under the levelling blows of stroke after stroke, he spends long stretches of time in partial paralysis, struggling to form full sentences, unable to produce new work with his former proficiency and flair. On each occasion, Florence assists his slow recovery. They talk together, muddling through. He sits at his type-writer, brittle and straining, using a single finger to press each letter-key. Around his feet, a pile of ripped and crumpled pages, broken words.

~

Near the finish, history is made. The Soviet pilot, Yuri Gagarin, becomes the first human to orbit the earth, on the successful Vostok 1 space-flight. News of his triumph storms the globe, to be met with exultation by cheering crowds (and trepidation by American military planners). On an April morning, Bill yelps with joy as he reads the New York Times report, as if Gagarin's excitement were his own. In the coming days, he resolves on a fraternal ode: in praise of this courageous cosmonaut, who

... floated

ate and sang

and when he emerged from that

one hundred eight minutes off

the surface of

the earth he was smiling

Called “Heel and Toe to the End”, it is one of his final poems, and most beautiful. The New York Times quotes Gagarin himself, reading simply: “I Could Have Gone on Forever”.

~

“Then he returned / to take his place / among the rest of us”

~

Innumerable writers pay tribute after his death, including Robert Lowell. Like Denise Levertov, Allen Ginsberg, and the anarchist troubadour, Kenneth Rexroth – all of whom, to varying degrees, are antagonistic to Lowell's poetic school and style – the Boston poet combines the personal affection of a protegé with the admiration and sincerity of a fellow literary practitionner. “Williams is part of the great breath of our literature”, he says of the departed elder; in a culture “dense with the dirt and power of industrial society”, the doctor strove to witness and rejoice. An apt aubade.

~

Even today, the poems can startle, with the free-wheeling vitality of their perceptions, the affirming force of their beliefs. We come to share their rapt surprise – at all this vividness, all this life. We step inside, and wander gladly. The kindly doctor leads the way. Why do we follow? Because the world wakes up when he hear his voice, when we sound his words afresh.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mike Davis, Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx's Lost Theory (Verso Books, 2018).

James Laughlin, Remembering William Carlos Williams (New Directions, 1995).

Robert Lowell, Collected Prose (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1987).

Paul Mariani, William Carlos Williams: A New World Naked (Trinity University Press, 1981).

Alec Marsh, Money and Modernity: Pound, Williams, and the Spirit of Jefferson (The University of

Alabama Press, 1998).

William Carlos Williams,

— : Autobiography (New Directions, 1951/1949).

— : Litz, MacGowan, eds., Collected Poems I: 1909-1939 (New Directions, 2000/1991).

— : MacGowan, ed., Collected Poems II: 1939-1962 (New York, 2000/1991).

— : MacGowan, ed., Paterson (New Directions, 1995/1992).

— : Selected Essays (New Directions, 1969/1954).

— : Thirlwall, ed., Selected Letters (New York, 1957).