- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

Work & Witness: A Note on Apolitical Poetry

In a recent interview with The Nation magazine, Carolyn Forché exposed and dissected one of the reigning presumptions of the contemporary Anglo-American poetry-scene: by addressing what she termed “the fiction” of the “nonpolitical or apolitical [literary] work”. Specifically out-dated and objectionable, she said, is “the idea”:

that somehow there’s this little hermetically sealed egg that the poet writes within, uninfluenced by any events, by his or her time, outside of anything but this hopelessly solipsistic self… I think that’s changing. That notion is breaking down.

Admittedly, few (if any) writers have championed the view of poetry that Forché criticised in exactly the terms she chose for them. But she nevertheless identified what is a prevailing (and stubbornly resilient) trend of thought associated with the literary establishment, i.e. among poets and others who are paid by publishing houses, universities, reviews, literary foundations, and the like, to read, teach, assess, and write about poetry. Many of these, undoubtedly, have themselves produced sophisticated and interesting work in the art, but this shouldn’t be taken to mean that there are no discernible patterns of stance and interpretation in the opinions these same figures promote in their capacity as ‘poetry professionals’.

Were we to look, we’d find in one well regarded publication (deemed by some to be “the premier British poetry journal”) a 2019 editorial arguing for writers to be judged by the “revolutions in craft” they attempt and achieve, while dismissing so-called “identity politics” and the “politicised aesthetics of the day” as illegitimate barometers of creative value. Walt Whitman is praised for “inventing the American line” and using it to write “through to his subjects and his forms”; Adrienne Rich is then cited as a poet of comparable merits, and on the same grounds (i.e. for bringing the technical range of the English-language canon to bear on her own themes). In a similar vein, a former editor of Poetry Ireland Review has indicated a disdain for the notion of political verse (“I come out in a rash at the idea”), saying that:

Poetry’s response must be to remain true to itself rather than rush into rhetoric…. Language is hugely important in and of itself and not just as a vehicle for communication. Attention to language can change the experience of life.

Noteworthy, in both cases, is the obvious fact that in rejecting the supposed narrowness and ideological prejudice of a “politicised aesthetics”, the editors simultaneously concoct a rather blinkered and didactic paradigm of their own. They are, needless to say, entitled to do so, and should not be silenced (whatever this would entail) – although their propositions can be critically examined.

While I don't subscribe to the theory that poets should have the last word on the work they create as an absolute rule (see below), I'm conscious, reading the editorial pronouncements above, of the ways in which Adrienne Rich herself conceived of literary craft. Far from being defined by its textual innovations alone, poetry, for Rich, was part of a collective “refusal to let our humanity be stolen from us”, and indeed could be understood as a kind of “connective strand between unlike individuals, times, and cultures”. Near the end of his life, Whitman, also, was clear in expressing his discomfort with “the doctrine (you have heard of it? It is dinned everywhere)” of “art for art's sake”, believing as he did that “Literature” should be written and celebrated primarily as “a means whereby men may be revealed to each other as brothers.” It seems that the much-vaunted “American line”, for Whitman himself, was a means to an end (i.e. towards realising a more democratic culture), and not the final measure of his work.

One (to my mind) particularly stimulating intervention in the fray of this debate was made by Eavan Boland – whose poetry may be read in some respects as an adaptation of the subversive energies and excursive example of Forché, Rich, and other canon-questioning American poets to a range of historical and biographical subjects. “I know there has always been a theme in the self-definition of writers that suggests the only responsibility they recognize is to write well”, she said:

But even with these primary concerns, surely there must be some room [for] those words calling and warning us to keep vigil at the boundaries between expression and silence, to patrol the line carefully between aesthetics and ethics? Calling and warning us to understand our responsibilities to both.

Attentiveness to the “writer’s work”, Boland continued (partly echoing Forché’s desire for a poetry “written in” and through “the aftermath of extremity”), should not be used to delegitimise or distract from “that much more elusive thing: the writer’s witness.”

Curiously, perhaps, in his essays and lectures, Seamus Heaney seems to have leant in the opposite direction to Boland here, instead situating the gravitational centre of poetry in its formal shape and linguistic texture. “Poetry cannot afford to lose its fundamentally self-delighting inventiveness”, he once asserted, favouring “its joy in being a process of language” over its potentiality “as agent for proclaiming and correcting injustices”. In this view of the craft, he admitted, “there is no hint of ethical obligation”: an apparent lacuna compensated for, he suggested, by the writer’s new-found access to the “innate capacity”, the self-sustaining amplitude and complexity, of the poem itself – as a vibrant, textual entity.

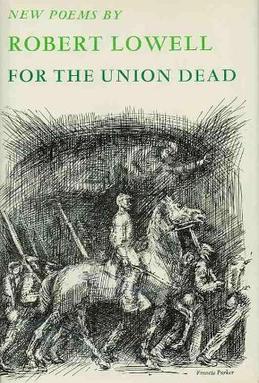

Heaney repeats this tactical pivot dexterously across his critical work: acknowledging the writer’s position in a range of civic and political contexts, and then subtly rejecting any conditioning or compelling relationship between those contexts and the writer’s craft, which is thought to be a private matter. So, for him, the richness of Robert Lowell’s late work is “all there, in the mouthing of the syllables”, “fruity” and “custardy”, the verse a simmering stew of verbal “events rather than the record of events”. According to Heaney, Lowell's most fully realised poems are expressions of a self liberated from history, abstractions that the poet-critic anchors by offering an aestheticised account of his personal (and apparently epiphanic) reading of the American writer’s work, with the insinuation that this repeatable encounter is where poetry's universality is rooted.

Derek Mahon’s alternative interpretation of Lowell may be worth mentioning, as a counterpoint to Heaney’s argument. Of the poem, “For the Union Dead”, Mahon observes:

Lowell is saying, among other things, that America has become a nation of slaves to the system, contra naturam, that the system requires continuous institutionalized violence (Vietnam) and that older values are now out of reach… ‘savage servility makes the wheels go round.

Mahon was writing a memoir of time he spent in America in the 1960s when he made these remarks. So the essay turns to Lowell's work as a way of commenting on Mahon's own experience, while also casting the American poet as a critic of empire: motivated by a deep sense of history (the civil war) and a prophetic perception of the violence and degradation of contemporary events (Vietnam). He seems to approve of, and be fascinated by, the fact that the self-examinations expressed by Lowell in verse also provide a portrait of his society: a society Mahon comes to see (through the poem) as being built on “institutionalised violence” and “wage slavery”. In an apparent inversion of Heaney’s approach, Mahon’s discussion is concerned to formulate an understanding of the inner world of the writer and his oeuvre in light of the collective political and social concerns of the epoch, collapsing the division between the two and implying that poetry can be a portal into life at large, and other lives.

All of which cleaves to the grain of Lowell’s work: a poet who seemed always to write (and with increasing audacity throughout his career) by bending the canonical and technical apparatuses of his craft to the quaking visions and shattered reminiscences of his own life, until a new equilibrium was either reached or broken. Heaney’s parallel parsing of Lowell's literary catalogue for verse that “does not flex its literary muscle”, but adopts an “unemphatic tone” as it becomes “beautifully equal to its occasion”, arguably evades and misconstrues as much as it illuminates.

It should be said that the approach and professed outlook of Heaney the critic – above and in general – may also offer a misleading impression of Heaney the poet. It’s certainly possible to interpret “The Republic of Conscience” as an exercise in formal mastery, for example, an evolved meta-commentary on poetic technique. But to disdain or ignore the paradigm of moral imagining and social projection developed in that piece would be critically doltish – an ideological indulgence masquerading as news.

If anything, the seemingly private sorrow and self-recrimination coursing through Heaney’s poems are so memorable (and at times, searing) because of the depths of ethical understanding revealed by their flow and gleam. “Hercules and Antaeus” is not only a re-casting of canonical myth in a localised dialect and landscape, although it is partly this, but a parable of world-historical dispossession. Hercules’s strength and guile are civilisational in their grandeur – “his mind big with golden apples, / his future hung with trophies” – and monstrous in their force and effects, as Antaeus’s defeat foreshadows the radical erasure, the permanent uprooting, of “Balor”, “Byrthnoth and Sitting Bull”, who all “will die”. The opening chords of Olympian (even, dare we say, imperial and Euro-centric) triumph dissolve, by the poem’s close, in a hush both bleak and visceral, as the recognition of vanished, deracinated indigeneity comes home. The loneliness of that loss, moreover, tacitly includes, casting into stark relief, the poet’s own – a point that may serve to counteract Ciarán Carson’s dismissal of Heaney (in 1975) as “the laureate of violence [...] a mythmaker” and “mystifier”. The vision-altering fog of lyric and myth is continually sliced, clarified and dispelled, in Heaney’s work, by the particulate devastations of home and history, which the poet registers with an almost physical intensity: as though he, too, had been wrenched permanently “out of his element / into a dream of loss // and origins”.

Roy Foster has spoken of Heaney’s self-awareness and unshowy ambitions as a master craftsman. The critical prescriptions of the essays and lectures may be understood as (semi-defensive) emanations of such a figure: deploying the resources and rigours of one intellectual milieu, the academy, in a manner that establishes a zone of flexible permission in another, poetry. Although often presented as forming an ars poetica, Heaney’s habit, as ‘professor’, of reinforcing the author’s right to pursue his craft (unencumbered by the expectations and “pre-approved themes” of others), should not be mistaken as an automatic signifier of the creative content and positionality of his poetry, which consistently explores the relationship between “work” and “witness” that Boland and others have openly affirmed.

Boland’s extended comments on the tangled questions above may offer a final, clarifying perspective. “We have to resist the pressures of a society that urges us only to value the product”, she suggested: “Only to honour what is seen, and can be owned and may be sold. Each of us [must] try to make our own democracy of creativity.” By presenting issues of authorial right and technical dexterity in the vocabulary of entrepreneurial activity and commodification, her comments foreground a key subtext of supposedly “apolitical” and anti-political poetics, whose advocates often inhabit positions of relative professional and financial security, and who justify such success, implicitly or otherwise, on the basis of their talent (rather than, say, their unquestioning acceptance of certain literary modes and mores).

In a society saturated by a neoliberal ideology that both masks and deepens existing inequalities in the name of competition, enterprise, and market values – pulverising common spaces and customs, as well as the very idea of democratic modes of production and organising – the pervasive discourse of elevated literary expertise and insular textual innovation cannot plausibly be portrayed as free of ideological implication and investment, or accepted uncritically. Witness, outwardness, connection, denunciation, response: these all are a part of poets’ labouring, just as lineation, language, and achieved soundscape are the techniques and materials they engage. We can attempt to create a “democracy of creativity”, or a self-referential potpourri of linguistic effects, but in whatever directions we decide to work, the choice is a political one. Poet-critics should desist from pretending otherwise.