- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

Sea Music

For several months now I’ve been listening and re-listening to a traditional Irish air, played by Martin Hayes, and for several months I’ve found myself entranced. Hayes no doubt deserves some credit; even to my untrained ear, his playing seems to have a suppleness, an instinctive access to tone and emotion, that draws out the vitality of the original music. But the song itself also has a hypnotic power. The tune is “Bony Crossing the Alps”, and was first transcribed (I’ve learned) in the middle of the 19th century, although its provenance, weaving in and out of folk and diasporic culture, likely stems from some decades earlier: specifically, when “Bony” (read Napoleon Bonaparte) and his troops traversed the Swiss Alps in 1800, with the aim of liberating Genoa from Austrian attack. The song pulses with the rhythm of history on the move, a world in motion, as well as a vim that implies a people, or a single consciousness, taking pleasure as that perception forms. Or so it sounds: less like a panegyric to Napoleon per se (as Jacques-Louis David’s hyperbolic portrait of the same event was intended to be, or Beethoven’s 3rd symphony partly was) than a stirred up lift-off of local, rebel energies.

Even if my subjective response to the song veers away from its actual origin and history (I’ll let the experts decide), the French army’s continental spread in 1800 had obvious implications for Ireland, adjusting to the brutal expansion of post-1798 military rule by the British empire – and despite palpable defeats, still a seedbed for subversive sentiments, land agitation, and patriotic discontent. To my mind, perhaps paradoxically, this turbulent vista is implied in the lightness of the march, the grace of its flight, and whenever I tune in to Hayes’s version, I sense the spectral presence of that atmosphere looming (large and complex though it must have been).

Some of the material signatures of that time are with us still. It was in the same period, after all, and with a similar intuition of the epoch-changing possibilities of a new France rising to its East, that Britain pioneered what was then a formidable mode of coastal defense, lining Martello towers (named after a fortification on Corsica’s Mortella Point) along the maritime borders of its global empire: from Australia to Sierra Leone to Ireland, where approximately fifty were built. Whether in Cork, Dundalk, or South Dublin, today for sea-swimmers, walkers, and local historians the towers are familiar features of the contemporary landscape, many of them having been converted into museums or tourist attractions.

The Martellos have also assumed a cultural and iconographic resonance, standing not just as monuments to a (now-distant) colonial imperative, but as emblems of modern literary imagining. Most famously, James Joyce’s novel Ulysses opens in a Martello, as a sleep-bedraggled, but nevertheless “stately” Buck Mulligan runs his “smokeblue mobile eyes” over the “snotgreen”, “scrotumtightening sea” of Sandycove, intoning in Greek, “Thalatta! Thalatta!”

My own favourite reference to the same tower comes in the prefatory note to poet Michael Hartnett’s translations from the Chinese Tao Te Ching, which he completed in 1963. “The imagery of the poem”, Hartnett writes (somewhat sweepingly), “is a mixture of Oriental, Occidental and mystical”, while the “landscape” evoked “is that of Sandycove, the tower and the sea.” As is equally true of Joyce’s work, the sensitivity to permanence and change (and maybe, also, the permanence of change) that shines through the subsequent poems carries with it the glimmer of such a spot-rooted understanding – as if all poetry and philosophy could, or must, stem from an appreciation of this corner, this abiding, sea-lit outcrop, of the Dublin coast. “I need never change my views”, one segment reads; another, that “I see only water, / yet there is soundless life beneath it.” Hartnett continues, “In my sea-house I never bolt the door, / yet only my friends can enter. / I sit on the rocks / reclaiming all that is worthless[.]” Although antiquated in some respects, the poem – its process of self-situating, of attention and tribute – is one I can’t help but value. I return to it often.

My own Martello (I always think of it as mine – as if it belonged to me, or me to it), my most regular and personally emblematic of stone squats, is not far away from the Joyce-Hartnett tower: in Seapoint. Occasionally, thirsting for a swim, I’ll cycle from one to the other and settle for whichever is less crowded – usually in the summer, when the long light draws people out, or if a race has been organised, in which case shoals of wave-heaving athletes descend on the water, splash-kicking its deep grey surface white. Of course, the fact that the sea is loved by many, and that South Dublin’s public bathing spaces are now open to all, is a glad sign of the times (my Mum still speaks of the atmosphere of menace and physical intimidation she encountered when she first tried swimming, as a woman, in the Forty Foot in the 1980s – with the result that to this day she prefers to bathe elsewhere). But as somebody whose preference is for immersion over exercise – a peculiar, and surely self-deluding, form of purism – I also like to savour the sea, floating, dipping and just generally rolling around, without having to make way or share! In or out of the water, it seems, I’ve convinced myself that I need my space.

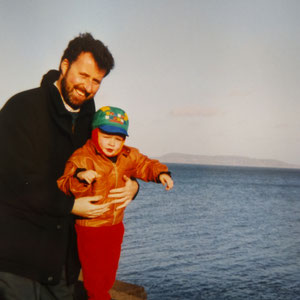

Strangely, although I’ve visited Seapoint all my life (and have been swimming nearby for most of it), I don’t remember anything of my first decade there. I know my family has a series of pictures of me, held in turn by my two sunny-eyed, fresh-faced parents (somewhere around the age that I’ve now reached), sitting on the sea-wall, a hazy Howth visible in the distance. But the moment itself, and the many others like it between then and my early teenaged years, is a blank: a memory I’m compelled to imagine and invent, rather than recall. (This said, I happen to think that all remembering involves some degree of fabrication, so that the past – if so monolithic a creature can really exist – is always at least partly conjured by the present, flickered through by the strange light of our most private and intuitive desires). In some respects this is a simple enough exercise. One of my firmest impressions of Seapoint is that the rhythms and rituals that play out in its shadow have taken root over a long period; the faces may change, but the impulse to gather (however separately) and to swim is surely no recent phenomenon. In other words, I can discern, if I need to, my younger self, and can reconstruct some semblance of my younger parents, in the families that come and go today, with the rest. Despite my proclaimed penchant for lonerism, then, it’s clear that whatever special experience of solitude the sea offers is also, for me, enhanced by the awareness that my own water-lust is far from unique. Innumerable others have felt the same way, and do.

If anything, there’s a pleasant absurdity, as well as a refreshing egalitarianism, to the community in Seapoint. For although its many visitors may not necessarily think of themselves in this way, we all become commoners (lovers of the naturally given and continually replenished commons of the waves) when we return: to strip ourselves bare and enter the water, so close to ice. Bank managers, barristers and judges, teachers and nurses, as well as retirees and in-betweeners (among whom I’ve counted myself more than once, on the dole, passing through, or just generally attempting to ‘figure out’ my latest life-situation): the social distinctions and stratifications that in many ways encode and define our day-to-day goings-on momentarily come loose, or seem to, as everyone steps past the Martello’s steps, and out to sea.

As it happens, I recognise a good number of ‘the regulars’ at Seapoint by sight, if only a few by name. Some have disappeared entirely. Barbara, whom I think of always as blue-eyed and briskly moving, ready to brave even the autumn’s sharpened waters; Rita, sparkle-faced and bustling, all chat, with Matt close by, quiet; Aengus, glamorously dishevelled (even in swimming trunks), and quick to smile. Thankfully, there are many others I still encounter in passing. And, however odd this may be, I take comfort from the combination of intimacy and near-anonymity that defines our relationship to one another. For these swimmers, I – otherwise a stranger – am at my most recognisable with my clothes off, if at all (no small statement). More than this, they surely understand only too well the secret that drives me back to our shared demesne: that I feel most myself, and very much at home, in my few minutes dipped below water, floating under the skies. In that sense, my fellow swimmers know me more than anyone, and yet hardly at all; as I do them.

This being said, and perhaps because of my love for poetry (my willingness to give in, indulgently, to its many temptations), I’m conscious that there’s a risk of aestheticising Seapoint and my experience of it – of creating an atmosphere of breathy, somewhat depersonalised reverence for the place, when in fact it’s the usualness there that I love, as the tide and its many guests arrive and leave, without surprise, predictably, season-to-season. And so when I say that I feel most myself when swimming (drifting, really), it’s not that Seapoint takes me out or away from the humdrum life that otherwise preoccupies me. Very often, the opposite is true.

Lately, for instance, I’ve felt a persistent flare of annoyance – anger dimmed down to a grimace – when I see, across the bay, the Poolbeg incinerator, a muscular plume of chemical smoke invariably billowing above it. If a symbol of our (somewhat degraded) civic sphere and its persistence in our supposedly private lives were needed, this would certainly suffice. Now operated by a US multinational company that specialises in converting “waste combustion” practices into profit, Covanta, the incinerator had been consistently opposed by elected city councillors when plans for its construction were advanced by government and the council’s own executive staff, who proceeded with the public-private partnership nonetheless. Ever since, the poisoned ribbon of cloud extending from the facility’s chimney has seemed to me not only a continuing health hazard to thousands of Dublin’s denizens (which it undoubtedly is), but also a kind of living memorial to what I'm tempted to call the connivance and arrogance of the state, its officials and institutions.

At the time that the waste facility had begun operating, in 2017, my own life had in fact taken an activist turn – which may explain my reflexive, somewhat dogged insistence on institutional and system-based causes for what would otherwise seem merely personal gripes and grievances. Curiously, as a result, the residual irritation I feel while swimming in sight of the incinerator (my sense of it as a somewhat toxic stop-gap, rather than the beacon of creative and sustainable planning that was surely needed) I associate with the propulsive rhythm of political agitation: writing leaflets, joining meetings, taking actions, learning the vocabulary of social change.

In truth, I frequently found the rigours of that weekly round exhausting, and was quietly awed by the combination of stamina and apparent glee that some of my fellow hell-raisers brought to the fray. More often than not, I stayed committed (insofar as I did) to the grand cause of exposing power and its ways, dismantling its many infrastructures, out of loyalty to the endlessly re-converging mob of subversives and idealists I was working with, rather than out of certain belief in the axioms we adopted as our own: chiefly among them, that socialism was somehow a historical or scientific inevitability (which rang to me more like an equation of abstract slogans than a blueprint for collective liberation).

Likewise, the pieties undergirding party organising – for I had joined a socialist-oriented political party – seemed designed to dress electoral ambitions and transparently self-promotional aims in (to my eyes) an ill-fitting revolutionary garb; and more generally to normalise the idea of a mass politics stage-managed and guided by a minority of enlightened strategists, an approach that smacked, too often, of self-delusion and intellectual snobbery. My consciousness of these contradictions in Ireland’s formal socialist movement, vying with (what remains) a genuine admiration for many of its members, germinated slowly, leaving me conflicted and sometimes depressed. Eventually, I came to doubt the value of my participation, and, rightly or wrongly, I stopped. But there was an immediacy and sense of necessity to the moment, while I was in it, and I often think back to the thrill of realising that the great tomorrow of radical political transformation had (and could only have) its beginning in us, me, ourselves, now.

Although not currently a political campaigner in any sustained sense, I nonetheless try to hold to this last recognition, in my work, my reading, my interactions with the people around me. In an oblique way, too, I believe it relates to a small happening, a ripple of urgency, that occurred the last time I swam in view of the Seapoint Martello, before the 2020 lockdown had fully commenced. That day, I found myself thinking, out of the blue, of the painter Sean Scully, or more precisely of an essay by him that I had read some months before – mentally reaching for his words, as I pulled myself against the cold, slow current, but unable to catch them exactly. When I returned home, I searched through my scrawling notebooks for them, until the passage I had struggled to remember came clear. What he said, what I had needed to hear without knowing, was this:

Life isn’t a straight line. It’s always folding back on itself. This makes it deeper and stronger. Nothing gets left behind; everything is continually gathered up and remade in the folding rhythms of its song.

And so it is that Seapoint, for me, is also where the ghosts come back; where everything gone is stirring still, like a wave-borne, Alpine whisper, filling the morning skies with music.