- Home

- About

- Company

- Essays

- Culture

- A Mosaic for Dr. Williams

- Movie Miscellany: 17

- The Shark Nursery by Mary O'Malley

- Movie Miscellany: 16

- Movie Miscellany: 15

- Trump Rant by Chris Agee

- The Invisible Heart: Katie Donovan

- The Letters of Seamus Heaney

- Movie Miscellany: 14

- Poetry and Power

- Dreaming Freedom: "A Change Is Gonna Come"

- Painting Light: Eilean Ni Chuilleanain

- Movie Miscellany: 13

- The Swerve by Peter Sirr

- Linton Kwesi Johnson: Revolutionary Poet

- Movie Miscellany: 12

- Cinema Speculation

- The Radical Jack B Yeats

- Movie Miscellany: 11

- Movie Miscellany: 10

- Fogging Up the Glass

- Movie Miscellany: 9

- Movie Miscellany: 8

- From the Prison House: Adrienne Rich

- Movie Miscellany: 7

- Robert Lowell & Frederick Seidel

- New Poetry: Reviews

- Movie Miscellany: 6

- William Carlos Williams's Radical Politics

- Movie Miscellany: 5

- News, Noise & Poetry

- Common Concerns: On John Clare & Other Ghosts

- Punkish Sound-Bombs: On Fontaines D.C.

- Movie Miscellany: 4

- Movie Miscellany: 3

- Deadwood: A Dialogue

- Movie Miscellany: 2

- Movie Miscellany: 1

- Kill-Gang Curtain: Night of the Living Dead

- "You can neither bate them nor join them"

- Our Imaginary Arizonas

- Storm Visions: Two Films

- Sleepless Nights: Three Films

- Green Bottle Bloomers

- Nightmaring America: A Love Story

- Thirteen Thoughts on Poetry

- Shakespeare's Precarious Kingdoms

- William Carlos Williams's Medicine

- Chambi's World

- Work & Witness

- John Clare's Journey

- On Seamus Heaney

- Shelley in a Revolutionary World

- “Mourn O Ye Angels of the Left Wing!”

- Derek Mahon's Red Sails

- Radio Station: Harlem

- Oak-Talk Radical

- Percy Shelley Questionnaire

- Smashing the Mirror

- Diamond Dilemmas

- Shelley's Revolutionary Year

- William Carlos Williams in Ireland

- Derek Mahon, Poet of the Left

- Memoir

- Politics

- Truth to Power: Interviews

- Culture

- Favourites

- Other

- Poetry

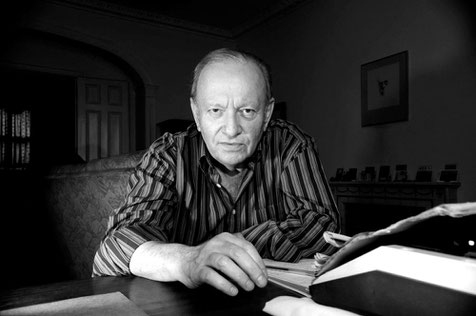

Derek Mahon: A Poet of the Left

(First published by www.independentleft.ie)

"I know the simple life / Would be right for me", writes Derek Mahon in "Ovid in Tomis", "If I were a simple man." A glad complexity, it seems, is the order of the day; a dynamic interweaving of expression and insight evident throughout Mahon’s work, lending the poems both a clarity and a frequent mystery. "It is not sleep itself but dreams we miss," Mahon posits (with aphoristic aplomb), "We yearn for that reality in this." Known for his intellectual force and technical fluency, and admired as a translator from multiple verse traditions, the Belfast-born poet is universally recognised in establishment literary circles as a leading figure of his generation and moment. Less mentioned, however, is that – in its breadth, emphasis, and overarching perspective – his work invites celebration and cultural co-optation by socialists, anarchists, and every species of utopian realist in between. For although formally traditional, his poems are critically incisive and, in brief, radically human to the core.

It’s a point that’s seldom heard, and so, perhaps in a small way, worth reiterating. Insofar as the ethical compass and content of Mahon’s poetry are discussed at all, the conversation tends to be couched in a discourse of reflexive academic qualification: so that the specific details of Mahon’s political commentary and commitment at any one point in his poetic career are presumed to be offset or made redundant by his aesthetic, philosophical, or even formal concerns at another. We are left with a "poet of divided affiliations," who maintains "a cautious distance from schools and groups (whether literary or political)," his stylistically graceful poems "characterised by indirection and obliquity," even as they depict (occasionally) a "humanity… powerless against the inevitable forces [that] shape human life." We end up, in other words, with a political poet, but one whose work is said to exceed its own politics: thus transforming the latter into an empty category, rimmed by abstractions such as The Force of History or The Demands of his Time.

Such a trend, of course, arguably relates to culture in general, and not to the work of Mahon alone. It would certainly be a tempting thesis to explore: that in a neoliberal society, art and literature are circulated in order to be owned, to placate, or to make life as it is (exploitative and miserable as it may be for many) more liveable – and not to subvert the tenets by which that society is organised. In which scenario, what we think of as literary criticism would in fact amount to nothing other than a series of discursive adjustments and revisions, a sort of academic vanishing trick whereby whatever creative radicalism was identified in an art-work, oeuvre, or historical moment would disappear as soon as it was declared. Sound familiar?

At any rate, for gentle-hearted heretics of all stripes – anti-establishmentarian in their politics, but nevertheless in need of the emotional and critical sustenance that literature provides – there is surely some merit in re-examining the work of poets, great and mighty, and the inherited assumptions that frame our encounters with them. In Mahon’s case, moreover – a writer who calls himself an "aesthete" with a penchant "for left-wingery […] to which, perhaps naively, I adhere" – doing so helps us to reach a fuller and clearer understanding not only of his literary back-catalogue, but of the power systems that rule and rack our present world. This may seem like high praise for one of Ireland’s more canonical of contemporary poets; but it’s also true.

Take Mahon’s book, An Autumn Wind, in which we find the artist’s inward vision turning to survey, with searing perception, a global vista defined in the main by corporate theft and murderous imperialism (headed by the USA). "The great Naomi Klein," he writes,

[…] condemns, in The Shock Doctrine,

the Chicago Boys, the World Bank and the IMF,

the dirty tricks and genocidal mischief

inflicted upon the weak

who now fight back.

Mahon’s praise (indeed, rather pointed name-dropping) of Naomi Klein surely gives credence to his self-proclaimed status as a political Leftist. But it also draws a question mark over the standard critical narrative outlined above. Far from deploring modernity in the abstract, shaped by some equally vague "inevitable forces," Mahon’s verse here associates directly the neoliberal economic doctrines of "the Chicago Boys, the World Bank and the IMF" with crimes against humanity, while also acknowledging both the theory and the praxis of resistance that such doctrines inadvertently generate (typified by Klein and by "the weak who now fight back," respectively). It is difficult to imagine Seamus Heaney or Michael Longley, the two most-fêted of Mahon’s Irish contemporaries, advancing such a perspective.

It is notable, also, that the much-touted "concern for the ecological" in Mahon’s later work exists, in the poem above, within an explicitly anti-capitalist paradigm. Close-focusing on a "hare in the corn / scared by the war machine / and cornered trembling in its exposed acre," the piece in its closing stanza switches to a wide-angle lens, so to speak, and urges that in the next "spring, when a new crop begins to grow, / let it not be genetically modified / but such as the ancients sowed / in the old days": a possible retort to the criminal policies of the agri-corporation, Monsanto. What’s certain, however, is that this is a poetry that arrays itself against (and takes aim at) neoliberalism per se – or what Mahon terms, in his resonantly titled poem, "Trump Time", "the bedlam of acquisitive force / That rules us, and would rule the universe."

Without wanting to over-extend the argument, there’s also a refreshing contemporaneity and excursive quality to Mahon’s range of reference here. Although he may indeed be a literary practitioner combining "classical structure with contemporary concerns" in his work (read great, white and male) – his "precursors" including "Samuel Beckett, Louis MacNeice, the poets of Rome and Greece" – in this instance Mahon openly, and quite self-consciously, takes his cues from a feminist critic of modern capitalism, herself writing of a number of (highly gendered) grassroots movements, primarily in the Global South. Feminist icon he is not, but Mahon’s work at the very least points towards an intersectional understanding of economic exploitation and political struggle: as companion poems in the same volume (such as "Water") arguably also testify.

None of which is meant to create a further barrier between the so-called aesthetic merits and political commitments of Mahon’s work. If anything, it’s to argue that these qualities exist in continuity with one another, and to suggest some ways in which the overtly political interventions of Mahon’s verse may be seen to sharpen what one authority has described as the "crystalline clarity" of its intellectual make-up, giving heft and consequence to the "sophisticated sound-patterning" for which his poetry is so often admired. Mahon’s bright-soaring, early imagination of an art drawn "From the pneumonia of the ditch, from the ague / Of the blind poet and the bombed-out town" – one envisaged as bringing "The all-clear to the empty holes of spring, / Rinsing the choked mud, keeping the colours new" – was always grounded not just in the sensations of a literate intellect, but in a sensibility disposed to compassionate identification with the realities of other people’s lives: in a word, to solidarity. For Mahon, equipped as a writer with the same "light meter and relaxed itinerary" so beloved of countless literary fence-sitters, the urge that recurs most persistently is in fact "To do something" – or "at least not to close the door again" on those condemned to live "in darkness and in pain."

On a final note: this short sketch has tried to claim Mahon as a poet of and for the political Left: a loose but very real community, whose existence is rarely questioned except by a few faction-feasting personages who are already in it. In doing so, however, we would do well to remember that the democratisation of power so often promised and struggled for by activists holds exciting possibilities for poetry, too: its creation, its reception, and (again) its circulation. As Mahon’s homage to Shane MacGowan implies, the list of great poets can and should be appreciated "together with the names Seeger and MacColl": dissident troubadours both, although generally lacking from Mahon’s academically prescribed influences. Art is what we make of it, in short, and the broader the field of shared endeavour, the better. So let the task be to reap and sow the commons of poetry and song, if for no other reason than to pay tribute to Mahon’s work and in the same spirit that the work itself proclaims.